The Parthenon - a case for Theory in Architectural Conservation

By Kin Hui

Abstract

Abstract: This essay is to examine Parthenon in Acropolis, Greece in relationship to the current theories of architectural conservation and to explore how the theories are applied internationally and locally.

I visited the Acropolis in one summer when taking my first degree of architectural study in the university during the late 80s. I had chosen Athens as the first destination in my trip to Europe. The cover page in this essay is a watercolour picture of mine, depicting the side view of Erechtheion in the Acropolis. I can still vividly recall the visit after so many years. Climbing the ramp and numerous steps at the entrance gateway (Propylaea), it heightened a sense of pilgrimage to Acropolis. The sun was high up against the pristine sky. Upon reaching the top of gateway, it revealed vast expanse of the complex on a gentle sloping ground. Standing obliquely on the left, its main building, Parthenon, greeted the visitors with façade of columns in a fashion of receding perspective. Le Corbusier, in his formative years, made a visit to Acropolis in 1911. He produced numerous sketches, writings and photos during his trip which were later published in his book Vers une Architecture (Towards a New Architecture). He wrote beautifully in his admiration of the complex. “The Greeks on the Acropolis set up temples which are animated by a single thought, drawing around them the desolate landscape and gathering it into the composition. Thus, on every point of the horizon, the thought is single. It is on this account that there are no other architectural works on this scale of grandeur. We shall be able to talk “Doric” when man, in nobility of aim and complete sacrifice of all that is accidental in Art, has reached the higher levels of the mind: austerity.”1 It is no denial that the Acropolis captures immense number of architects and visitors their imagination of the splendid Greek civilization. That summer, I was reading the book, Republic, written by Plato. The dialogues in the book, together with my previous visit in Acropolis, etched deeply in my mind of the intellectual and free spirit that Socrates had instilled in his discourse with disciples during its ancient time.

HISTORIC EVENTS

Acropolis means ‘high city’ in Greek. It was built in 490 BC shortly after the Athenians won the war against Persian invasion. It was built to commemorate their victory by dedication the temple to Athena which was the city god of Athens. The assembly of Acropolis consists namely of four buildings, including the Parthenon, Propylaea, Erechtheion and the Temple of Athena Nike. Parthenon is the largest temple in the complex, built entirely in marble.

To facilitate the building of Parthenon, builders quarried their marble in nearby Mount Pentelicon which was about 16km from Athens. Being an icon of classical antiquity of the ancient Greek culture, the Acropolis was subjected to ravage of time throughout the centuries. In AD 267 the Gothic Herulians invaded the lower city. The Acropolis was converted into a fortress by the Romans. With the advent of Christianity during the seventh century, Parthenon was transformed from a pagan temple into a Christian church, first as a Greek Orthodox church and subsequently into Roman Catholic after the Crusade by 1200s. Constantinople was fallen into the hands of Turks in 1453 with Athens a few years later. The Parthenon became a mosque with the addition of minarets under the reign of Turks. A catastrophe took place in 1687. In the battle between Venetian and Turks, bombardment ignited the gun powder stored in Parthenon, triggering a serious explosion. Parthenon was badly damaged with its central portion being blown apart. In Figure 4, a picture taken in 1804 showed the condition of Parthenon with remnants of the mosque still in the foreground of the picture. Decay and loss were inflicted on Parthenon which was subjected to random vandalism in the following years after the explosion.

By 1800, the French army invaded Egypt which was under the Turkish empire. The British then drove the French out of Egypt in 1801. As a return of gratitude to the help from British, the Turks granted permission to Lord Elgin, who was the British ambassador to Turkey at the time, to excavate the site. Lord Elgin seized the opportunity and took away extensive valuable sculptures which are in the present being displayed in the British Museum of London. They become so called the Elgin marble.

Fig. 5 Drawing made in 1674 of the west pediment of the Parthenon, depicting the contest of Athena and Poseidon for the patronage of Athens.

PARTHENON AND ITS CONSTRUCTION

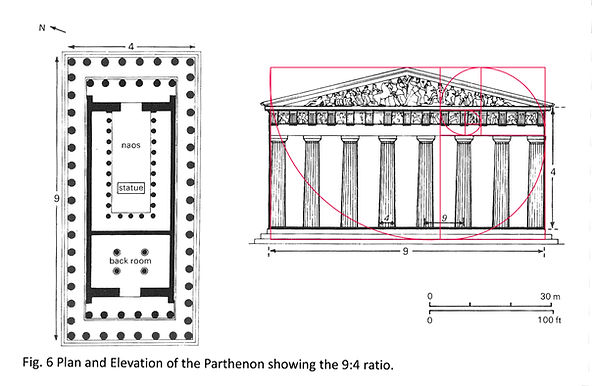

The construction of Parthenon commenced in 447 BC and it was completed by in 438 BC. Its construction is basically in post and lintel with peripheral columns supporting an entablature. There are eight columns at both ends and seventeen on the longitudinal sides. Its stylobate (the top slab of temple base) is measured by 30.88 metres wide and 69.50 metres long. It follows a proportion of 9 to 4 which becomes the basic guiding principal proportion for the temple. The columns are in Doric order with diameter measured at 1.91 metres where they rest on the stylobate. The columns are in height of 10.43 metres. Fig. 6 shows the plan and elevation of Parthenon in the proportion of 9:4. Its simplicity in the form carried a strong coherence and harmony that are derived from mathematics. As the temple was built during the pinnacle of Hellenistic era, its construction highlighted the refinement and elegance of the Greek civilization. Le Corbusier elucidated eloquently about its composition. “ From what is emotion born? Form a certain relationship between definite elements: cylinders, an even floor, even walls. From a certain harmony with the things that make up the site. From a plastic system that spreads its effects over every part of the composition. Form a unity of idea that reaches from the unity of the materials used to the unity of the general contour.”2

EARLY ATTEMPT OF MONUMENT CONSERVATION IN 19th CENTURY

In 1833 the Turks withdrew from Athens with the surrender of Acropolis. Eventually, the Acropolis was free from foreign rule. The Greek Archaeological Service began with the works of excavation and conservation. As a historical monument, the Parthenon laid with its sublime beauty in aesthetic as originally conceived by the architects in the Hellenistic era. On this aspect, the conservation team in the 19th century found no compromise with the alteration and addition carried out by the Ottoman Empire. The mosque that was once sat in the centre of the Parthenon was not considered to be reconstructed in any form. This can also be explained on the aspect of outstanding universal value. The Hellenistic culture is tangibly associated with the value of Democracy and Philosophy. But one may argue with this purist approach. With the advent of 20th century, there is change in theoretical principles on international level with re-focus on cultural heritage over time in relation to original and subsequent characteristics.3

One major mistake was committed during the early attempt of conservation works in the midst of 19th century. The ancient Greeks had marble fixing with iron clamps encased in lead for prevention from rusting. Balanos, the engineer in charge for conservation in latter part of 19th century, did not follow the ancient practice exactly. Instead, he placed steel bars which were usually used as reinforcement in his days without any coating protection. By the 20th century, his metal clamps began to rust which posed threat of marble splitting which needed urgent rectification works.

MONUMENT CONSERVATION IN 20th CENTURY

In 1977 UNESCO (the United Nations Educational Scientific, and Cultural Organization) began with an international campaign to rescue the monuments on Acropolis. The conservation was re-examined in the limelight of contemporary theory of conservation. Up to the present, a series of charters as guiding principles have been formulated over decades - the Athens Charter in 1931, the Venice Charter in 1964, the Burra Charter in 1979, and the Nara Document in 1994. Scholars, for example Alois Riegl, Gustavo Giovannoni and Casesari Brandi, put forward their theories relating to preservation and restoration in the contemporary context. Modern aspects of heritage and conservation include authenticity, integrity, modern science and technology, cultural diversity and legislative control with strategies taking place within a framework of multi-disciplinary practice. In 1984, it heralded in an extensive phase of restoration works in Parthenon which has lasted for several decades and is still ongoing in the present. This generates a good opportunity to evaluate the works based on the contemporary theories of architectural conservation.

THE ATHENS CHARTER AND ANASTELOSIS

The Athens Charter was published in 1931 after the First International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments. It includes in its article VI for the technique of conservation the wording ‘Anastelosis’. It is a methodology followed throughout in the conservation process for Acropolis. Originally, anastelosis is an archaeological practice of reassembly fragments of ancient artifacts. Its application in architectural conservation emphasizes on the use of original building materials for conservation of monuments as in the conservation for Parthenon. The article VI stated that ‘In case of ruins, scrupulous conservation is necessary, and steps should be taken to reinstate any original fragments that may be recovered (anastylosis), whenever this is possible; the new materials used for this purpose should in all cases be recognizable.’ For the case of Parthenon, I will be explored in details regarding the relationship of anastelosis with the concept of authenticity and integrity in the context of 20th century.

CONSERVATION THEORY AND AUTHENTICITY

I am intrigued with Immanuel Kant with his writings on “Critique of the Reason”. In some certain ways, the concept of “Kunstwollen” of Alois Riegl is related to the philosophy of his predecessor in the search for truth. Riegl expounded the concept of plurality of values, including antique, historic and intentional commemorative value. In term of conservation, they correspond to the judgment on authenticity and integrity of a historical building. In Greek, authentikos is associated with genuineness, uniqueness, and truthfulness in stark contrast with copy, reproduction and counterfeit. Therefore, presence of the original is a precondition required for authenticity. In the case of Parthenon, the top priority on the agenda in restoration works during the 80s was not to have any works jeopardizing the original structural philosophy of Parthenon. Interventions were limited to the absolutely necessary to respect the ancient structural system 4. They were also concerned with misplacement of original stone works that were executed by predecessors during the 19th century. Special computational programme was formulated to assist in re-matching the pieces with their original positions. In restoring peripheral colonnades, new marble was to be quarried from the same quarry that was used in the ancient time. Scattered fragments were meticulously returned to their original positions, following the practice of anastelosis.

Mechanical copying machines, known as pantographs, were deployed to form new completions to match the damaged original members. In the recent phase, the restoration team collaborated with provider of CNC machine to develop model that could deliver completions with quality and accuracy of the final products comparable to pantographs. This practice of combining new stone pieces with the original fragments becomes the significant feature of anastelosis for Parthenon during the 20th century. For works that could be well executed manually, techniques and tools used in the restoration works were similar to those of the ancient craftsman. All these efforts were endeavoured to achieve the best result in conservation works for alignment of authenticity of the monument, and its process corresponded to the quality and refinement as exemplified by the original architects of Parthenon.

INTEGRITY AND ENTASIS

The unique beauty and visual integrity of Parthenon was also encapsulated in the minute curvature along the height of columns. The effect is so called “Entasis” which is an optical refinement to serve as reverse illusion to facilitate the temple to be viewed as intended. Studies were made to investigate how the ancient people could manage to achieve this accuracy and subtle curvature. For restoration works, an industrial fixture was deployed for the measurements both of the diameters and the heights of the drums to enable perfect match for the profiles of the columns flutes with variation in heights.

INTERGRITY AND REVERSIBILITY

Reversibility was also called in to maintain its structural integrity for the future generations that might involve in any conservation in years behind. Technique of dry fixing was adopted and no chemical material as surface preservatives would be allowed for the sake of its reversibility in the long-term guarantee. For the fixing clamps, the steel clamps installed during conservation works in the 19th century were to be replaced with new metal elements. The conservation team collaborated with the National Technical University of Athens in the field of advanced metallurgy. The new connective elements were made of titanium with strength equivalent to the original iron clamps that were used by the ancient builders. This would guarantee the new clamps not to rust and fail in the long run.

INTEGRITY AND THE CONCEPT OF PATINA

In Figure 9, we could discern clearly the new parts with the original marble by their difference in colour. It was well noted that the conservation team intentionally kept the patina of original marble so that it could bring out the contrast between old and new in alignment with article VI of Athens Charter. Patina refers to the fading, darkening or other signs of age which is the natural part of the original fragment. It is distinguished from dirt or dust gathered on its surface. This strategy of preserving the patina endeavoured to maintain the integrity of Parthenon as a historic monument. New elements take up lesser extent than the original without obscuring the wholeness of the original structure.

VALUE OF MONUMENTS WITH THE SURROUNDINGS

Gustavo Giovannoni, an Italian architect by the turn of 20th century, had the concept concerning value of the area and its surroundings. This sets out the criteria to have any addition not to detract the monuments “from its interesting parts, its traditional setting, the balance of its composition and its relation with its surroundings” 5 as stipulated in article 13 of the Venice Charter in 1964. It led to the subsequent formulation of legislature with designation of buffer zone and the imposition of obligatory control on any building or development within the boundary of Acropolis. There is also another legislature which declares the Acropolis area a no-fly zone.

CESARE BRANDI’S THEORY OF CONSERVATION AND THE CONCEPT OF LACUNA

It will be interesting to note that Cesare Brandi, an influential figure on historic conservation by mid-century, commented on “ruins to be consolidated as such” in his Restauro Critico. We can view that the objective in carrying out the works on Parthenon in the last few decades is to consolidate the ruins in lieu of reconstruction. It is no doubt that the restoration works is to prolong the life span of the existing Parthenon structure which has been ravaged over the centuries by human as well as by natural catastrophes. This strategy of minimum intervention has been commonly practiced in various heritage sites in Greece and Rome which are the very countries in the West that are still richly endowed with antiquities these days. It leaves room for imagination by visitors to revive the original conditions in their mind in lieu of material reconstruction in entirety.

In formulating the principle of conservation, Brandi stated that ‘any integration must always be easily recognizable, but without interfering with the unity that one is trying to reestablish. Thus, at the distance from which the work of art will be viewed, the integration should be invisible.’6 In the other words, Brandi’s theory requires the additions to be distinguishable from close up but render invisible from a distance without distracting its unity as a whole. In alignment with Brandi’s theory, we can discern the overall result of conservation for the Parthenon in Figure 9 with the new parts not overtaking the original fragments.

For the illustration of the above, Brandi adopted the word ‘lacuna’ (missing part). The word of lacuna is originally used for conservation of artworks, particularly for historical paintings. It requires for the missing parts to look like the background without distracting the viewer from seeing the original artwork. In a historical painting, the lacuna shall take up a neutral tint, consisting of small dots or stripes (the tratteggio technique). Seen from a distance, the colours and the tonality must fit the original, but from close up tratteggio creates the necessary difference from the original. 7 To apply the concept into architectural conservation and restoration work, the reconstructed parts shall no larger in size than the original parts without the whole appearing like a copy or reproduction. Therefore, it ties in closely with the concept of authenticity. It also correlates to the article 13 of Venice Charter in regards to the balance of composition for monuments. Besides, we can also extend its meaning by referring to the empty space or missing parts in the Parthenon. The lacuna encapsulates the ravages of historic events on the monument.

But Brandi’s theory may not be universally applied throughout the world. For example, Japan has the deep-rooted tradition of disassemble and reconstruct their timber monuments over the centuries. In the early 2021, they has just completed the re-assembly in its entirety for the east pagoda of Yakushiji (薬師寺) which has its original structure dated back to 680 AD. It goes with the fact that Japan has been successfully in pasting down their traditional craftmanship, particularly for carpentry, over the centuries. Their original timber structures were built with the technique of groove and socket construction without the use of any nail or fixing screw at all. This provides for replacement and reconstruction in their posterity. Therefore, as opposing to the globalization, contemporary conservation theory witnesses the growing trend of phenomenon to respect cultural diversity in formulating preservation and restoration strategy. For this, we can find out in the Burra Charter in 1979 and the Nara Document in 1994. 8

The End